Disclaimer: these tips are mainly for on-piste advanced carving skiing. But I honestly think that the best skiers are the most complete ones. I strongly agree with the following:

“The best skiers are the all-around skiers… The guys that are able to rip in the park, rip in the woods, rip powder, rip everything. They are just very good natural skiers”.

Quite a few skiers can carve a turn… but to bend a deeper tighter arc? only the experts…

One of the things that expert skiers have in common is that they can build supreme edge angles in the turn (like you see in the World Cup!). Why they would do that? Well… in short, just to make the shortest radius carved turn possible. In a carved turn, the more edge angle you produce, the more the ski will bend, and the shorter the radius of the generated arc. Edge angle is the most important factor to determine how much a ski will bend. The load is secondary, and it is created mainly by the skier’s natural weight balancing on the ski. The amount of this load depends primarily on the skier’s speed. advanced skiing

But first things first. What is edging? Edging is the ability to tip the ski on edge and adjust the angle between the base of the ski and the snow. In common words, it is tipping and un-tipping the skis. We edge the skis either to turn or to slow down (or both). Most recreational skiers change direction and slow down at the same time (skidded turns), but racers typically change direction without slowing down (carved turns). In a carved turn, the tail of the ski follows the tip in the exact path/groove. This type of turn requeires edge engament or edge lock (I.E. locking the ski onto edge).

When tipped on edge, the ski bends because of its “hourglass” shape. If you take one ski, lay it over flat, and then tip it, you’ll see that only the tips and tails touch the ground/snow, and the middle part of the ski remains “in the air”. With the skier’s weight, the ski bends until the middle part touches the snow too. The higher the edge angle, the higher the amount of ski bending, and thus the tighter the turn radius.advanced skiing

Generating this amazing angles correctly during a turn means keeping always our balance over the outside ski. Balancing predominantly over the outside ski is the most efficient and stable way to turn. To illustrate it, imagine we are running straight down a flat, empty street and want to change direction suddenly, we always lean on the outside leg to push and move sideways. So we balance on the opposite leg to the side we want to go. Or in other words, on the external leg. That is the most stable and efficient way to change direction. In skiing, it’s just the same.

It is important to note that, in order to generate outside ski pressure, we have to think in terms of BALANCE. And we should balance mainly on the outside ski but in an indirect way, that is by unweighting the inside ski.

Skiing is all about balancing while in motion. Skiing is the ultimate balancing act. The focus in skiing is to stay in balance into the future!

“Anybody can carve, right?. But can you bend a tight deep arc? That’s what it’s all about…

In my humble opinion, the ten most important elements for achieving that “full range carving turns” correctly are:

1) High speed (and/or steep slopes)

To turn with huge edge angles while keeping balance over the outside ski, high speed (or a steep pitch) is mandatory. We need the strong G-forces (tangential inertia, actually) generated by the high speed that moves our balance out, to the outside ski. It is key to getting those big Edge angles to generate high G-forces throughout the turn, so we can really move our Center of Mass inside the turn while maintaining balance over the outside ski.

Just to clarify, the outside ski is the ski farthest from the center of the turn. Conversely, the inside ski is the ski closest to the center of the turn. In other words, the outside ski is the ski that is in the outermost part of the turning arc.

If you don’t have enough speed, and try to build those big angles, you will end up with your balance over the inside ski… not good at all… so in order to practice it look for a well-groomed not too crowded intermediate run where you feel comfortable with, and you can generate speed safely. advanced skiing

2) Hip-width stance

The stance (that is how wide the feet are apart while skiing) should be “hip-wide”. It is very important not to widen your stance width more than that. During a turn, the skis should have predominantly vertical separation, not horizontal… Horizontal separation (the stance) is how wide the feet are apart. In a good athletic stance on skis, the distance your feet are apart should be no different than that when you’re standing, walking, running, or also while standing on your skis on a flat hill.

The vertical separation of your feet is the distance in height, one foot to the other. While skiing, vertical separation of the feet is constantly changing and is directly related to the edge angles that are developed. Vertical separation is usually the greatest at or just after the apex of a turn when a skier is resisting the combined forces of gravity and centrifugal force. It’s at its least during the transition phase between turns.

When you shorten your inside leg, you move the skis away from each other, but at a vertical distance. As mentioned, if you make the mistake of separating your skis horizontally (“widen the stance”) and then crouch down to build the angles, you will end up having your balance over your inside ski, and that’s not good at all… in this situation, the inside ski will be right under you and your center of mass (also known as the core of the body, which generally lies between the navel and the spine). Also, you will get not parallel shins, with way less edge angle in the inside ski compared to the outside one (A.K.A. “A-frame”…). Remember, we always have to look for edge similarity from inside and outside ski.

In summary, a horizontal stance that is too narrow will limit balance, foot independence, and the ability to use the inside ski. Also, a horizontal stance that is too wide will cause an incorrect balance shift onto the inside ski and limit inclination. In addition, the “hip width” stance is the one that allows for faster and simultaneous feet rolling and edge changing during transition.

3) Strong inside inclination (AKA “toppling”) at the beginning of the turn

The most crucial aspect for building huge angles is to really “throw” yourself sideways to the inside of the turn at the very beginning, by extending/pushing with the outside leg and at the same time flexing/shortening of the inside leg, thus then letting yourself fall to the inside of the turn by means of gravity (AKA “toppling“). Having said that, it is very important to note that this toppling happens after we build or establish the new platform on the new outside ski. So, Early Weight Transfer and Early Platform Establishment over the new outside ski are key in order to then being able to topple quite, as needed. In other words, “first find the new ski, the new platform, and then topple in…“

Toppling at the very beginning of the turn means allowing gravity to make us “fall over” to the inside and thus create ski angles fast as we move the base of support (the skis) away from our center of mass. This movement definitely feels like a “falling over”. We fall, fall and fall, and then the forces catch us and we remain upright.

So, to allow us to generate an upcoming very high edge angle on the skis, it is mandatory to topple in and move the skis away from us. We need to move the skis out and away from our body to develop big edge angles, there is no other way. To have the greatest edge angle possible I need to put my legs almost horizontal, and to achieve that I have to have my feet out and away of my pelvis.

This movement of toppling will be followed by increasing upper body angulation to keep our balance on the outside ski as we progress in the turn. If not, we are at risk of “prendere una internata” or “perdere l’esterno” as Italian coaches describe the sudden shift of balance from the outside ski and onto the inside one.

This strong and on-purpose movement to the inside needs to be learned and practiced a lot, and somewhat feels like moving into an unbalanced lateral position, but believe me, it is really important in order to produce huge edge angles, later on in the turn.

We can clearly see it in the picture below of “Mr. GS” Ted Ligety. Something interesting to mention too is that he has only a little upper body angulation out, and still keeps his balance on the outside ski. How’s that possible? It is because he is carrying a huge amount of speed… don’t try it at home…

We need to move the skis out and away from our body, in order to develop big edge angles.

As Ted Ligety himself talked about it in an Instagram Live with Jonny Mosely:

“One of the most common novice questions people ask me is regarding how much weight on each ski… And I never think about it but it’s pretty much 100% on the outside foot. But you’re never thinking what the percentage is. It is over the outside ski where you want to be!“

By the way, Jonny Moseley says mogul skiing is just the same, 100% from outside ski to outside ski. More quotes on that:

“The foundation of skiing has always been on the outside ski, and we must ingrain that”.

“It is so important to make sure you are on your outside ski and as soon as you possibly can be. All of your speed comes from the pressure you can produce on your outside ski to get it to bend in a really short period of time. ”

4) Shortening of the inside leg by flexing it

To accomplish those great angles, the key is to shorten/collapse the inside leg by flexing the inside HIP and KNEE while moving to the inside of the turn. Flexing the inside leg drags the pelvis both down and in. That’s the holy grail, flexing/shortening the inside leg deeply (bending it a lot). The more you shorten the inside leg, the more you’re going to “fall” and move to the inside of the turn, and the more edge angle you’ll be building. This “falling to the inside” happens naturally and passively by shortening the inside leg. It’s the continuation of the toppling as a “free fall” of the body to the inside of the turn. To move our center of mass further inside the turn and achieve those angles, we must deeply flex the inside leg to “get it out of the way”. If we don’t do that, the inside leg blocks the ability to move further in.

The highest edge angle is achieved when you have (briefly) your inside hip touching or rubbing the snow. That happens at (or a bit after) the fall line. This skiing movement of progressively moving to the inside of the turn by shortening the inside leg is similar to what happens if you cut and shorten one leg of a standing ladder. The whole ladder is going to tip/move to that side…

This movement of flexing the old outside/new inside leg actually starts at the end of the old turn in order to generate an Early Weight Transfer into the new stance ski (new outside ski) even before the edge change. That is even before starting the new turn. That’s the way to get really early pressure on the new outside ski, because we balance on that ski even before it becomes the new stance ski, and that’s why the “Up and Over” drill is so good and so important in the World Cup athlete’s regular training. So, Early Weight Transfer and Stablishing an Early Platform with the new outside ski are key movements to set the turn for high edge angles.

Again, flexing the inside leg throughout the turn in a relatively narrow stance generates a vertical separation of the skis (not horizontal, so please do not separate your legs to get angles). Take a look at the picture below of Ted Ligety (credits to the great author and person Ron LeMaster). We can also note that the limbs are close together…

In ski racing nothing happens because it looks good, it’s all about performance… the best performance possible…

Skiing for the most part is about balancing on one leg, the outside one. That’s the more efficient way of turning. So regarding pressure, the inside ski is light and somehow “comes along for the ride”.

In addition, it is simply way harder to balance on the outside part of the foot (that happens when we balance over the inside ski) than on the inside part of the foot (that is balancing over the outside ski).

In case you have any doubts, let’s take a look at the image below:

Stefan Rogentin of the Swiss Ski Team really arching that outside ski… Also take a look at the flexing pattern, deeply flexed on the shovel, and straighter in the tail of the ski. The majority of the skis are designed to behave like that (softer shovel, harder tail) to facilitate turn initiation and increasing the speed going out of the turn.

As well as flexing, the inside leg must tip to the inside of the turn to build the edge angles. The tipping always start from the inside foot and ankle, by rolling them in (actually, the foot and ankle can only move just some milimeters inside the ski boots, so it is more of an activation of that muscles than a huge movement).

The inside ski tipping leads the tipping of the outside ski (and not the other way around!). If you try to tip the skis with the outside ski first, you’ll get the “A-Frame” problem mentioned above, because the inside leg does not follow the outside one regarding inclination. So in order to have similar edge angles on both skis or what is the same to have parallel shins, we need to always tip from the inside foot/ankle/knee (and in that order of importance). Take a look at Allie Resnick of the US Ski Team demonstrating this beautiful SL turn. Note the similar edge angles on both skis:

Regarding leg activity, in high-level skiing we focus (or pay attention) more on the inside leg work, than the outside one. While skiing down the slope, we tend to focus mainly on flexing and tipping the inside leg, and that’s how we, indirectly (and almost automatically) get pressure and angles on the outside ski. The inside leg is way more active than the outside. And speaking in terms of balance, to go from outside foot to outside foot during the turns, we have to work mainly with each inside leg by unweighting it. So high-level skiing is really about inside leg active performance. advanced skiing

Actually the focus is on the lifting of the whole inside half of the body, which is in charge of creating the major movements. This way we create perfect balance on the outside foot, which remains always as the dominant balancing ski.

So even though the outside leg is the dominant regarding balance/weight, it is not in terms of movement. In Alpine skiing, the inside leg does much more active work.

One key aspect: In the first third of the turn we move our whole body inside (I.E. “inclination or toppling”) to create edge angles early. But this early inclination starts from tipping the feet, ankles, and knees to the inside, and not from the hips! Take a look at the “park and ride” error at the end of this article..

“In skiing everything starts from the ground up, from the feet up…”

5) Upper body angulation

This is another key aspect. In solid skiing, we need to move the upper body to the outside of the turn strongly in order to maintain outside ski dominance. Angulation starts early but is at its maximum in the second part of the turn and involves making angles with the body. It is created primarily at the hips. The more you do this, the more outside ski pressure you’re going to get. To achieve it, sometimes it helps to try to “lift” the inside shoulder up, or even better, try to “lift” the inside hip up (AKA “hip hike“). When you look at an advanced skier, it seems that the torso stays “still” from one turn to the other, since the upper body does not appear to move. The upper body remains relatively calm and still, relative to the movements of the lower body. This can confuse the observer, as it is actually quite the opposite. While looking quiet, it is actually rather active. The appearance of a quiet upper body is just that, an appearance. So the inactive upper body is an illusion caused by actively doing something.

So to generate upper body angulation, you need to actively move your torso to the side, to the outside of the turn. The more you tip your skis in, the more you have to side crunch with your torso (“bring the ribs to the hips”). It is crucial to train and strengthen those muscles involved, at the gym (the obliques and the transversus abdominis).

In the snow, practice it by exaggerating (a whole lot) the exercises that work on that skill specifically. There are a lot, but the “Scholpy Drill” is one of the best. Erik Schlopy is a former Olympian and actual U.S. Ski Team Coach.

Greek-American World Cup athlete AJ Ginnis at the 2023 Vald’isere Slalom showing great upper body angulation. Note as well the parallel shins. His style is not only very effective but a beauty to watch as well.

5.1) Upper body counter-rotation:

This means turning or rotating the torso opposite to the direction of the skis. Only the torso, NOT the pelvis/hips. We do it through spinal rotation. It is particularly useful in short turns, steeps and bumps skiing and it allows for better edge hold and greater upper body angulation angles, and faster turn transitions because of the undinding effect. We should start the counter as soon as we start the turn. You’ll note that upper body angulation will be easier to perform. In fact, in short turns upper body angulation and counter go kind of always in tandem. But remember, counter is done only with the torso, and never withe the hips/pelvis, which would produce the common “twisting at the hips” technique error.

IMPORTANT: That being said, it is crucial to differentiate that short or Slalom turns require a lot of counter-rotation (upper-body always “stable” facing the valley), but long or Giant Slalom turns require less or almost none counter-rotation at all. advanced skiing

Counter-rotation of the upper body was first developed by the Austrian instructors in the 1930s, as opposed to the “French” school that, at that time, used the rotation of the whole body as a unit or block. This French technique involved starting with a slow counter-rotation of the upper body (as a sort of a wind-up) and followed by a quick rotation of the whole body into the turn. By the way, this technique described in the written ski teaching manual “Ski Français” by Emile Allais in 1936, involved teaching beginner skiers to ski parallel without the use of wedge or stem christie turns.

So in advanced skiing, we look for “UPPER-LOWER BODY SEPARATION“: the legs and feet are tipping and turning one way and the upper body is tipping and turning the other way, for a complete separation (that is lateral separation + rotational separation).

“The first thing you could do in a corse is tightening your core, get a solid upper body position and keep it that way the whole way down.”

Take a look at this next image, an excellent photo montage of Ted Ligety on a GS turn. We can see the strong inclination (whole body tipping in) in the first two frames. After that, upper body angulation starts and gets really extreme towards the end of the turn (last frame), as Ted Ligety (AKA “Mr. GS“) has us used to see in his beautiful skiing style… This is actually the front cover of one of the best ski technique books ever written. I strongly recommend all passionate skiers to read it. Thanks Ron LeMaster for this masterpiece!!!

“In advanced skiing, while the upper body looks quite, it is acutally turning opposite to the lower body. The upper body does not move or rotate in space. It is actually moving or rotating relative (and opposite) the the lower body. “

In the next picture, Jett Seymour from the US Ski Team starting a right turn (AKA Left-footer or left-footed turn) showing extreme counter-rotation of the upper body or typically referred to as just “counter”. Note how the upper body is pointed in a different direction than the legs/skis. advanced skiing

6) Fore-aft aspect

Skiing is all about balancing while in motion. Skiing is the ultimate balancing act. The focus in skiing is to stay in balance into the future! In order to keep fore-aft balance (AKA being “centered“), we need to have our center of mass over the base of support (our feet).

In order to start a turn effectively, we need to move our Center of Mass forward to bend or balance over the front of the outside ski. We must start the turn by engaging the tip, so we look for “getting to the front of the ski” at initiation (AKA Early Weight Transfer). Moving our Center of Mass forward means moving our pelvis/hips over our feet. And we have three distinct tactics to achieve that:

1) Moving our whole body forward through ankle flexion: this one is a bit slower and takes more effort.

2) Pulling our feet back: pulling our base of support back is faster and requires less effort because of the lower mass of the legs compared to the whole body.

3) A combination of both: this one is my preferred way.

Moving CM forward at initiation is key to:

- Get tip pressure to allow the ski tip to enter the snow and excavate a groove for the rest of the ski to follow (I.E. carve the turn). Getting the ski tip to engage at initiation is essential for achieving a good turn.

- Be centered (I.E. pressure the middle of the ski) when we arrive at the most important part of the turn: the loading phase. The loading phase is when we apply almost all the pressure and the major ski deflection occurs. In the modern slalom technique (SL turns), the pressure or loading phase is short and abrupt, and it happens all at once at the fall line (i.e. the apex of the turn).

Also, the movement of the center of pressure from the front of the ski to the tail is a movement that facilitates the ski arching. Utilizing the entire ski from tip to tail is crucial for high-level skiing. We use the whole length of the tool (the ski) in order to turn effectively. At the beginning of the turn we make the tip of the ski bite, at the middle of the turn the center of the ski, and at the end the tail of the ski bite the snow.

“Driving the outside knee forward at the start of the turn is key in order to press the front part of the ski, and so when you then drive the knees inwards, you get that ski tip to bite. In this way the skis initiate correctly and the rest of the turn gets a lot easier. So the first and most important thing for me is to get the tip to initiate, and that I do by driving the outside knee forward first, and then in. Every turn starts like that.

A lot of recreational skiers are too stiff in their knees and there is no knee drive forward, so they get no pressure of the shin against the tongue of the boot.”

Skiing, unlike the majority of sports, is a super counterintuitive activity and you have to work against basic instincts (like self-preservation) to get better at it. In order to get pressure on the front part of the ski (the shovel) and successfully initiate a turn, we need to move our Center of Mass forward at the beginning (“high C”) of the turn. This means in the steeps to “face the danger” and “dive into the abyss”. Yes, leaning downhill goes against all common sense at first. It is definitely counterintuitive, but mandatory for good skiing and/or to ski in control.

So, CONTROL is all about good turn initiation, which is achieved by counter-intuitive movements. Good turn initiation means achieving a round (“capital C” letter) turn shape which directly relates to speed control.

If we happen to be in the backseat, and unable to load the shovel at the start of the turn, we end up with Z-shaped turns and poor speed control. In this wrong type of turn, we do all the edging and pressure all at once and very late in the turn. Here, snow spraying off the skis is directly downhill, and the line of descent is straight down the fall line with almost no lateral offset of the skier. That’s why we look to pressure our shins against the tongue of the boots at initiation, but that’s only at the beginning of the turn.

Fore-aft balance is dynamic, not static. It is in a constant cycle. In normal high-level skiing, skiers always go from being back at the end of one turn to being forward at initiation of the next turn. Pressure translates from tip to tail throughout the turn. Again, the key is being centered at the fall-line.

The use of the tails at turn completion is unquestionable. So being back at transition is absolutely normal, and kind of looked for.

As we already discussed, we use the whole length of the ski in a high-performance turn.

Being always forward is a mistake as bad as being always back. Fore-aft balance is dynamic, a constant cycle from front to back to front, and so on.

I honestly think several Ski Instructors Associations have to get better at this… Because I still hear on the slopes quite often: “you have to be always forward to have control”… One of the most world-spread misconceptions ever…

As Mikaela Shiffrin on an interview (here) said:

“The key for fore-aft balance, for me, is to try not to stay in one position. Because skiing is such a fluid sport, you’re always moving. And if you become static with your fore-aft balance, then the rest of your turn is going to be static. So, it’s really important to be able to be forward at the top of the turn and then try to use the rear of the skis. Not the tails really, but you know let your skis kind of shoot out from under you a little bit. Just try to play with the entire ski because you have a whole ski for a reason. You want to use the whole thing as a tool. And if you can use the tip-to-tail perfectly and be in balance, then you’re going to have a faster turn.”

“If everybody’s trying to whack super hard forward all the time and just hold that it’s physically impossible with the forces, and so you have to allow for the range of motion. It’s okay to get to the heel as long as you don’t stay there, and it’s the same thing if you’re always going to be hanging out in the front of the boot, that’s actually just as bad as being back. So range of motion is something that is really important and always something that you have to allow for because that’s how you create movement..”

In the photo above we can appreciate Mikaela Shiffrin finishing an SL turn. Please note how balance is mainly on the tails of the skis, with the tips actually elevated up in the air. Note as well the amount of counter-rotation of the upper body.

Another excellent tip comes from River Radamus, a U.S. Ski Team GS World Cup athlete: “When I’m entering into a turn all I’m thinking about is pulling my feet behind me. That move really flipped the switch for me in years past. Pulling the feet behind me is such a clear sensation for me and allows me to be at the front of the outside ski, to do the top of the turn right.”

River Radamus arcing a GS turn with his unique style. Note the eye-catching hip drag.

Being always forward is a mistake as bad as being always back. Fore-aft balance is dynamic, a constant cycle from front to back to front, and so on.

I honestly think several Ski Instructors Associations have to get better at this… Because I still hear on the slopes quite often: “you have to be always forward to have control”… One of the most world-spread misconceptions ever…

One important consideration

The discussed key tips number 3, 4 & 5 are regarding the lateral balance. Tip number 6 covers the fore-aft balance aspect.

From my perspective, it is essential to note that these movements of moving our CM forward, toppling the body in, shortening and tipping in of the inside foot and leg, and the upper body angulation to the outside is not a sequence of movements. They are a combination of movements, so they start more or less together at the same time and progress together as well. Also, these movements (and particularly the ones that influence lateral balance) increase in amplitude progressively, as the turn develops. They progress until three-quarters of the turn, when they reach their maximum range (except for moving forward of the CM, which only occurs during the first part of the turn).

Skiing is a fluid performance of combined and complex movements that all happen simultaneously in a relatively short period of time. We only isolate them in order to study them thoroughly and/or sometimes to train them (for example, when we use on-slope specific ski technique drills targetting certain skills). That’s why the best skiers look so fluid while they are ripping down the mountain, and make it seem so easy.

From my perspective, it is essential to note that these movements of moving our CM forward, toppling the body in, shortening and tipping in of the inside foot and leg, and the upper body angulation to the outside is not a sequence of movements. They are a combination of movements, so they start more or less together at the same time and progress together as well.

Also, these movements (and particularly the ones that influence lateral balance) increase in amplitude progressively, as the turn develops. They progress until three-quarters of the turn, when they reach their maximum range (except for moving forward of the CM, which only occurs during the first part of the turn).

Skiing is a fluid performance of combined and complex movements that all happen simultaneously in a relatively short period of time. We only isolate them in order to study them thoroughly and/or sometimes to train them. That’s why the best skiers look so fluid while they are ripping down the mountain, and make it seem so easy.

7) Foot pressure translates from front to back throughout the turn advanced king

This tip could be numbered “6.1” because it is part of the fore-aft aspect in skiing, but I considered it so crucial and that’s why I gave it a whole number.

While the turn develops, the norm is that our CM moves backward and we end up finishing the turn with our balance over our heels and thus pressuring the tails of the skis. At the feet level, the balance point moves from the ball of the foot at the beginning of the turn, back to the heels at the end. That’s what happens naturally, even on short turns. In order to start a new turn again, we have to move our CM forward again, and so on.

One study published in 2010 by T. Keränen et all., compared two groups of FIS-Ranked athletes, group 1 ranked higher than group 2. This study demonstrated that both groups had the same kind of center of plantar pressure front-to-back movement, which is associated with the ski’s bending pattern during the turn. However the higher-ranked athletes were able to produce more force in the frontal part of the foot and to the ski tip, and their center of pressure trajectory had larger mediolateral movement than the lower-ranked group.

Thus, the better the skier, the more pressure on the ball of the foot is able to generate, and the more edge angle they produce as well.

The better the skier, the more pressure on the ball of the foot is able to generate at the begining of the turn, and the more edge angle they produce as well..

8) “Aggressive” mindset

High-level skiing requires a lot of attitude and self-confidence. That “aggressive” mindset (and eventually, aggressive skiing or AKA shredding*) is absolutely necessary to be able to “get to the front of the skis” on the steep pitches for example. That is to “move forward into the abyss”, in order to load/bend the shovel of the new outside ski and make good turns. Both intensity and “aggressiveness” while skiing are very important, and sometimes it’s what it takes for a seasoned skier to reach the next level. So go for it! Like in almost all aspects of life, attitude is everything!

*to SHRED: to ski or snowboard aggressively. It’s a Go Hard Attitude with a Conquer All mentality.

“Shred the gnar“: a term originally created by skaters, meaning to ride with exceptional speed, ability, or enthusiasm, especially in difficult terrain and conditions.

The term has become common in a variety of sports, including skating, surfing, snowboarding, and skiing. Regardless of the discipline, the meaning is the same. To shred the gnar is to excel when confronted with a challenge.

So, keep shredding out there!

9) Surface and equipment

As well, it is important to mention that we need a hard surface (hard-packed snow), sharp edges, and relatively stiff skis to be able to “hold an edge” while performing those big angles. Tuning the skis to keep them sharp is very important. Sharp edges help you carve better. Those big angles do require sharp skis in order to prevent the sudden loss of grip during that high-performance type of turn.

Binding riser plates (AKA “lifters“) help a lot in developing high-edge angles because they create more leverage. These lifters are pieces of material between skis and bindings that elevate boots farther off the skis and the snow. They also allow the skier to hold a steeper edge angle without encountering “boot out“. Boot out occurs when the side of the boot hits the snow, causing the ski to get knocked off edge.

Regarding the base surface, if it is soft we could end up disengaging the outside ski off the snow during the turn (“to lose the outside ski“, particularly in the second part). If we lose the support of the outside ski, what happens is that all the balance (or pressure) moves strongly and abruptly to the (otherwise unloaded) inside ski. It then makes the inside ski bend violently and carve a very short radius path (in Italian ski terminology, “prendere una internata“). Next, it is usual that we get thrown away with a 180-degree air twist and fall over our backs, with the associated dangerous whiplash. Unfortunately, it is a relatively common way of crashing for advanced skiers. advanced skiing

This video is an example of this type of crash experienced by French World Cup racer Thomas Fanara during a race:

Example of a high-performance turn:

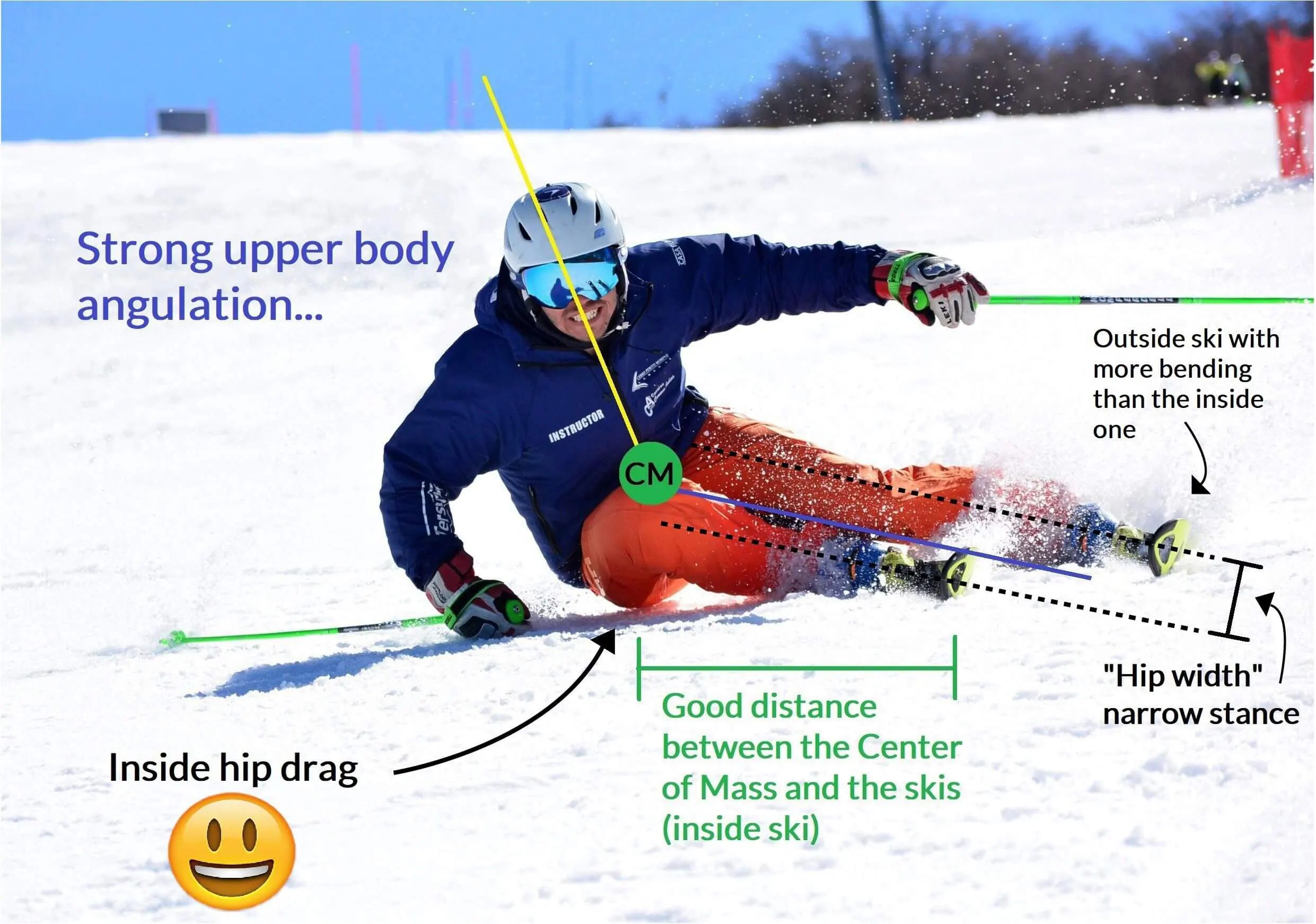

In the proper turn (figure 1), the skis (i.e. my base of support) are relatively far from my center of mass… and both shins are parallel, with similar edge angles in both skis. The inside boot is almost touching the outside leg (knee)… so my stance is actually narrow (“hip width”). The separation of one ski over the other is only vertical. Yet, because both legs are tipped to the inside, it “looks” like I would be using a wide stance, but that’s not true. It’s the exact opposite. You can see the strong upper body angulation as well. Also, we can agree that my balance is predominantly over my outside ski because it is clearly much more bent than the inside one. advanced skiing

Figure 1 – Skier: Federico Wenzel

P.S. you can also see my face with tightly clenched teeth because of the strong G-forces I’m experiencing (and trying to withstand) in that high-speed high-edge angle carved turn.

Generating those amazing angles while keeping dominant outside ski pressure is an advanced skill. That’s why the River Radamus (a US Ski Team athlete) #hipdragchallenge he did on Instagram was so successful and a beauty to watch…

10) Gradualness & progressiveness

The edge angle develops progressively, increasing continuously from the edge change until 3/4 (three quarters) of the turn, where it is at its highest. Then starts to decrease for transitioning to the next turn. We call that Progressive Edge Build, that is trying to progressively build that edge angle throughout the turn until we transition into the next one. We increase the edge angle smoothly and progressively from the ground up, from the snow up.

So edge angle is never static throughout the turn. That’s a typical error among intermediate skiers, that develop all the edge angles at once at the beginning of the turn, and then remain static the rest of it. They create angles by actively pushing themselves to the inside of the turn (instead of the correct way which is “free falling” of the body to the inside by shortening the inside leg). That common error is called “hip dumping” or “park and ride” style:

-Hip dumping: is when the hip puts the ski on edge rather than foot tipping. They just throw the hips in to create edge angles.

-Park and ride: when the skier builds all angles, in the lower and upper body, at the beginning of the turn and just rides the skis statically around the rest of the turn. Take a look at the next picture… advanced skiing

“Hip dumping” error

Here is another mistake, trying to generate big angles by crouching down over the inside ski:

Observe that his balance is mainly on the inside ski, which is right under his center of mass. His base of support (skis) is too close to the center of mass. He has different edge angles on both skis, and the stance is too wide (legs are too far apart). Look at the horizontal separation of both legs. The inside boot is quite far from the outside leg. Although funny, very far from correct technique…

Bonus tip: Really active skiing, keep yourself always moving

If you see racers (or ex-racers for that matter) freeskiing down a slope, you will clearly note that they are always moving. Always doing something. They don’t have any “dead spots”, nor moments where they become static, ever. They tend to perform extremely regular and rhythmic turns, no matter the steepness variations of the trail. They produce pretty much the “same” turn over and over, throughout the whole run. They really make it look so fluid and easy, but trust me, it is definitely not. That’s why racers (or ex-racers) are the best skiers. Because they train to turn where they have to, where the gates dictate it, and not where they would like to, as happens in free skiing. Furthermore, you can easily ‘train’ a high-performance ski racer to ‘demonstrate’ like a ski instructor, but it takes way longer to get a high-performance ski instructor to be a high-performance ski racer.

As the Italian legend Federica Brignone points out:

“Quando scio in campo libero è bellissimo e prima cosa è che cerco di essere con i piedi sulla neve sempre in ogni momento, e cerco di sentire che da una curva vengo portata nell’altra collegando senza avere un momento dove non sto facendo niente.”

“I really enjoy my free skiing runs, and first thing I try is to always have my feet on the snow at all times, and I try to feel that I am carried from one turn into the other, linking them, and without having a moment where I’m not doing something.”

Federica Brignone (AKA “La tigre” – the tiger) competes in all alpine disciplines, with a focus on giant slalom and super-G. Brignone won the World Cup overall title in 2020, becoming the first Italian female to achieve this feat.

I strongly recomend you to give it a try to the tips we discussed in this post, so then being able to reach that long-awaited “next level”…

Keep ripping some arcs!

If you find this piece of information useful to improve your skiing, please support this website and help us to keep it up and create more content! A small donation really means a lot to us... Thank you so much!

Great explanation.I believe that it is the most detailed article for achieving higher edge angle. Thank you for sharing. Could you please answer me if it is easier to achieve higher edge angles with Fischer Sc skis (165cm with 13,5m radius) rather than Fiscer Rc pro (175cm with 18m radius)?

Thank you in advance.

Greetings from Greece

Hello Velissarios! thanks for the comment. Regarding your question, it is easier to get angles with shorter radius skis. Longer radius, like GS skis, demand way more speed to get angles, and way more balance skills. Cheers from Italy!

During these deep carves, the uphill leg is bend close to 90 degrees or even deeper. I currently wear a boot with a 13 degree forward angle. When I bend the uphill leg deeply when carving it feels like the boot is blocking me and forcing me into the back seat. Is it fair to say that the reason racers wear boots with 17-18 degree forward leans is to allow them to keep their weight forward when the uphill leg is bend deeply?

Hello Jonathan, thank you for your comment. Yes that could be the issue, for sure. But try adding a velcro rear spoiler to the liners of your boots, and let me know how it goes. Let me know please. Cheers from Italy!!

Is there any device/exerciser on the market to help practice these skills during the off-season?

Hello PTP, that’s an interesting question. I don`t think so. But I can recommend this simulator, it is pretty accurate: https://www.skicosmos.com/ . Having said that, during the Northern Hemisphere off-season, you are in the Southern Hemisphere high-season. So you can come to ski and train in Argentina for example. Cerro Catedral in Bariloche is a great destination. Cheers, and keep ripping out there!

superbly written article. anyone approaching mid-to-high level ski will find a wealth of information. Donated – I know it’s not much, but it’s a small token of appreciation for such information. hopefully you will get as many clients/students as possible

Hello, Francesco. Thank you very much for your comment and your donation. Many hours are dedicated to creating this type of quality content. But my greatest motivation is to help many more skiers reach a high level of skiing, and be able to enjoy those unique and incredible sensations that only high-edge angle carved turns can produce. Cheers from Argentina and soon from Trentino, Italy!

Fantastic article! One area I struggle the most is applying enough pressure to the front of the foot at the initiation of the turn. I am using the Carv app and I get notification that I am applying more pressure on the hill. I am using the booster strap and keep them pretty tight. When I try to apply pressure to the front of my leg I feel like the strap is getting the pressure. I may be indirectly applying front pressure through booster strap but not directly with my feet. would love any advice

Hello Seckin, and thank you for your comment. Flexing the ankle/driving the outside knee forward in order to apply pressure to the front part of the outside leg and ball of the foot at turn initiation, remains the holy grail of advanced skiing. There are a lot of considerations regarding the equipment and/or technique in order to achieve this consistently. Regarding ski boots, adjusting the ramp angle in order to have pressure evenly over the whole front part of the cuff is key (and not only on the upper part, like you are experiencing). The order thing I would like to point out is that if the ski boot’s flex is too high for your ski level/weight, or if the booster is too stiff, you are not going to be able to flex the boot properly and transmit that load to the shovel of the ski adequately. So try to soften a bit and test too.

If you have a video of your skiing, I strongly suggest doing a video-analysis session with me or another professional in order to check on your skiing. Thanks a lot, and cheers from St. Moritz!

Great article from one of the best in the world. Fede, as an intermediate skier, I’m trying to understand ski carving biomechanics,

some instructors emphasize on “femur rotation” as main move, and effective skiing team on “ankle” rotation, as primary for edging, or is it a combination of them? Thanks

Thank you for your comments, Tito, I really appreciate them. Regarding your question, a very interesting topic by the way: what I think is that femur rotation is the main movement in order to move the knees in, into the turn. Because the knee joint cannot actually flex laterally. It is all made by femur rotation. But, having said that, the edging of the skis should always start from the feet and ankles, by tipping them in (supination of the unweighted inside foot is key). That is, for me, the first and foremost movement we should look for carving (and skidded turns as well). So to achieve edge angles we use a combination of whole body inclination, tipping of the feet and ankles, and moving the knees in by femur rotation. Hope that answers your question, and cheers from St. Mortiz #topoftheworld :-).

Excellent article, at age 75 skiing in Colorado I have been able to get edge angles above 50-55, and will keep trying all that you recommend. But remain puzzled still by the exact sequence of steps for turn initiation, apparently some of your suggestions are done simultaneously and others are sequenced. Have looked at a slow motion of turn initiation w commentary done by others but wondered if you could post a video about initiation with your excellent commentary.

Thank you for your comment Robert. And congratulations for keeping pushing it! I don’t really think it is a “sequence” of steps for turn initiation, I think it happens more fluidly and more less at the same time. But if I had to pick a sequence of movements, I would say that flexing to release the old outside leg, stepping on the old inside/new outside ski, changing edges, pulling both feet back, and toppling to the inside of the new turn by extending that new outside leg. Hope it helps! Cheers from St. Moritz!

This is an excellent article, one of the best pieces on ski technique I’ve read. Thanks Fede!

Thank you very much Kenny! Cheers from St. Moritz, Switzerland!

Wow, excellent description of just about everything that is involved in the turns pictured. Your entire library of articles is just like that – clear and comprehensive.

Have you thought about addressing the use of the arms at initiation in these highly dynamic turns? I’ve been working on lifting that new outside shoulder and arm at the top of the turn … at the same time as I flex the new inside leg. Moving that arm up in the air and tilting the shoulders into the turn moves my CoM over the skis faster and more dramatically. Theoretically this move should get my body entering the turn inclined as the WC skiers do in GS turns, but I haven’t yet had the gumption to let that arm raising produce that effect.

But the little “oomph” it gives me does get my CoM over the skis fast. Afterwards I progressively add the counter and angulation necessary to direct pressure to the outside ski. So far I haven’t felt the new inside leg supporting my weight, so I must be doing something right…..

And then there’s Ted’s swimming arms. I’d enjoy hearing you analyze that particular version of this arm raising.

Hello LiquidFeet, thanks for your much-appreciated feedback. Ted Ligety’s “pumping with the arms” technique is something remarkable, but as he said in an interview, he goes forward with the outside arm mainly for timing purposes. But only way after the apex of the turn, in order to not lean or rotate inside (what happens if you do it too early in a turn). Done correctly at the end of the turn, quote-unquote sets up your body to be in alignment for the top of the next turn and gets your hips through. Alice Robinson does something similar by the way. She had one of Ted’s coaches actually… cheers from Argentina!

Best post on how to be active with inside leg I have ever read. Thank you. Older skier that was coached heavily when younger on extending the outside leg and “throwing” cm into new turn but active inside leg was ignored resulting in ridiculous hip angles at top of turn that is neither efficient or particularly effective. Not trying to throw shade but dang PSIA seems to still have trouble getting hands around idea of active inside leg and vertical separation. This post combined with some Harb stuff and deb Armstrong stuff is getting this skiers hip to the snow. Thank you.

Thanks a lot for your accurate and thorough feedback, Bob. I do agree. The thing is once you hip-drag, you never go back! 🙂 Cheers from Switzerland

Good for old dogs attempting new tricks. I’m 82 year old hip dumping park and rider

Thanks Gary. Keep it up, and come skiing Argentina!

Nice write up. Clear, comprehensive.

Thanks Ed, hope it helps! Cheers from Argentina

very well written article, the only thing I would expand on is that you state in section 10 that maximum edge angle occurs at 3/4 point of the turn but dont explain why this happens. Given the article is all about achieving maximum angle why does maximum edge angle occur at the 3/4 point of the turn as opposed to the apex.

Great work !!

Thanks for your feedback Scott! Because three-quarters of the turn is where upper body angulation is at its peak, allowing for maximum edge angle while maintaining balance on the outside ski. Cheers from Argentina!

I think Fede is answering a slightly different question, “Why is it possible to achieve the highest edge angle…(at the 3/4 point)” rather than what I think might Scott’s true underlying question “Why is it necessary to achieve the highest edge angle…”

If so, my answer would be that at the 1/4 point, the force of the turn is partly offset by the force of gravity. At the 1/2 way point, the force you are trying to resist is entirely due to centrifugal force generated by the turn. At the 3/4 point the centrifugal force is augmented by gravity trying to pull you downhill.

By the 4/4 point your turn radius is increasing to infinity in preparation for tightening in the opposite direction, so there is no longer any centrifugal force. While the gravity force is now at a maximum, it is only 1G, whereas a tight turn could generate a further 2G or more.

Really good article.

yes…. this was truly helpful. Clear. Concise. Logical. Complete and thorough. Accurate. Myth-busting (eg. love the “wide stance” vs. “vertical separation” clarity)! Great videos and photo examples as well.

A fantastic piece for anybody to simply learn from and/or – for very advanced skiers and “skiing thinkers” – to confirm and better explain known coaching points.

Keep up the fabulous content!

Thanks a lot Kip for your thorough review of the post. Your feedback is very much appreciated. New posts are on the way! Cheers from Argentina!

Great insights/instruction Fede.

Thank you Frank, I’m glad you’ve found it useful. A considerable amount of time goes into writing this kind of post, so feedback is really appreciated. Cheers from Argentina!

As far as feedback, I had someone present the “leg shortening” advice during a level 3 alpine exam. That has never made a lot of sense to me. I’ve always thought that if you angulate, you’re inside leg must be shorter, or flexed. I got a lot more out of your explanation that your shins are parallel or how close your outside knee is to your inside shin, or even inside boot. I also took notice of how close your inside knee is to your chest. That alignment is important.

One other comment; I sent some bitcoin but not all readers have the capability to send crypto (at least here in the US). A paypal or venmo address might generate more payments?

Thanks Frank, that’s great feedback! Thank you very much for your donation. Yes, there is actually a PayPal donation button before the bitcoin donation QR. Maybe it is not clearly visible. I’ll work on that, thanks!

That’s totally my fault. I didn’t see it. Thanks for the content. When you get to Beaver Creek I’d like to see you ski!

Thanks Frank! It’s a true possibility to be in the Rockies next season for me. But come to ski Argentina in August. You won’t regret it!

Wanted to thank you for helping me get to the next level in my ski technique.

My pleasure S White! That’s my main goal. Help skiers get to that next level of enjoyment. Cheers from Argentina!

Absolutely fantastic article! The most comprehensive breakdown of advanced carving technique I’ve seen. I immediately had to share it with my online ski group. Thank you!

Thanks John! yes please, feel free to share it with your friends and family. We should help every intermediate skier to get to the level of enjoyment that only carving “arc to arc” turns can give you. That’s one of my main goals as a ski instructor!

Cheers from Argentina!

Indeed probably the best article i read so far on advance carving (quite comprehensive and with very useful examples …). Maybe there is one area to develop further around not letting the inside leg moving forward during the turn but overall awesome content !! Please continue to post new articles 😉

Thanks a lot Michael! for sure that’s a very interesting aspect of high level skiing! I will definitely add it to the article, in the near future. Thanks for pointing that out.

Cheers from Argentina!

Excellent article! One area that could be developed further is when and how to pressure the ski. It can be confusing to hear that the skier should NOT push out(and hip dump) but rather tip the ski on edge. So when the skier does pressure the edge where does this force come from in the body, what counters that force to keep balance, and when should it be done?

Thanks for your contribution Jason! In my humble opinion, how much a ski bends, depends much more on the amount of tipping (edge angle), and very little on the amount of pressure applied. Very little pressure is needed to bend the ski when it is tipped on edge.

So to carve a closer path, we need to strongly tip the skis on edge.

The tangential inertia is very much responsible for pressuring the skis during the turn.

Cheers from Argentina!

By far the best and. Most precise description I have ever encountered 😎👌

Thank you Henrik! I’m glad it was useful for you. Mote content is comming! Cheers!

Superb description in detail that makes sense. Given me some great tips can’t wait to put them into practice on my next trip to the home of skiing (Val d’Isere)! Cheers

Thanks Darren! I’m glad it was helpful, and I agree Val d’Isere is one of those places you should definitely go and ski, for at least 10 days!

I’m ski coaching in the Italian Dolomites now (Madonna di Campiglio area).

Cheers from the Dolomiti di Brenta!

At least from where I am at in my edge angles, this is perhaps the best, easy to understand description yet. I feel my muscle memory is so entrenched that it is hard to get past a certain angle. Going to focus more on inside leg and see what I can get.

Thanks a lot for your feedback, it really encourages me to keep writing new blog posts. I’m glad it makes sense. I must confess that while the inside leg activity is the key aspect in high-level skiing, in order to get more edge angle you need to “fall” to the inside of the turn more. Keep in mind that in order to keep outside ski balance, you will need to counterbalance your upper body to the outside of the turn.

The more you shorten (flex) the inside leg, the more you are going to “fall” to the inside of the turn, and the bigger the angles you generate.

Please try it, and don’t be afraid of going outside your comfort zone… that’s the way we improve and learn new movements and feel new sensations.

Cheers from Argentina! See you on the slopes!

I have been skiing for five decades, and yet it was only earlier this season that I worked out for myself that the inside leg is all I need to think about. *

It felt like such an important discovery, and yet no instructor had ever told me that (and I myself qualified as an instructor four decades ago).

And now that I no longer need the advice, here you are giving it to me. It feels like wonderful (and welcome) confirmation that I’m onto something important. Thanks so much!

*Actually not quite true. It is entirely true, for me at least, in relation to edge angle, though. For reasons I won’t go into, I still need to remember to slide my outside foot forward progressively and powerfully throughout the turn.

And to keep pressure on the ball of my outside foot’s big toe. I always knew I *should* do that, but (again) I only just worked out *why* : it’s for the benefit of the inside (medial) leg muscles of my outside leg. By firing them, my knee is stabilised to the point where it feels thirty years old (better actually, because I had weak medial quads at thirty, having been walking “flat footed” all my life)

Andrew, what I think is that progressive flex of the inside leg builds up progressively higher pressure over the outside foot. Cheers from Argentina!

Indeed, but what I had not realised until I worked it out earlier this year was that by concentrating on edging the inside ski, the outside leg would automatically follow, instad of being blocked by the inside knee being in the way.

I agree 100% with that. The edging needs to come from the inside foot and leg. The outside one will follow automatically and the shins will be parallel. If we look for edging with the outside foot/leg, the inside ones will not copy the outside one, and A-Framing will happen, with that blockage in edging capabilities. Thanks for your great insights! When are you coming to ski Southamerica? Cheers!

One of the best if not the best description of high performance basics! Thanks?

Thanks a lot! It took a considerable amount of time to write it. But it has everything I humbly and strongly believe of what “high-level skiing” is about… cheers from Argentina!

Excellent description of efficient skiing and easy to understand and spot on !

Thanks a lot for the feedback, Richard. I’m glad it was useful. New posts are coming soon. Stay tuned! Best regards…